The Monetary Policy Doom Loop

On the curious absence of capital and technology in models for monetary economics, and its nasty real-world consequences.

Last month, I wrote about two novels. The characters in those books were pursuing goals that proved unattainable, or worse, led them astray. That notion of ill-conceived goals will again be front and centre, though this time in a very much non-fictional setting: central banking.

Monetary policy is a keenly goal-oriented project: inflation, and perhaps output, is to be stabilised around a given value. But I believe that central banks at times shift their own goal posts. They behave, in a certain sense, like the donkey in the picture below: They pursue targets that are not static, but moved, unwittingly, by their own actions.

The fiscal policy doom loop we already know

At least since the Great Financial Crisis, it has been a point of discussion that policymakers might be unconsciously moving their own targets. This idea has so far mainly been applied to fiscal policy. In a paper fittingly called “Fiscal Policy, Potential Output and the Shifting Goalposts”, Antonio Fatás laid out the mechanism: Fiscal policy makers in Europe are usually bound by some rule limiting their ability to make debt. The amount of fiscal leeway they have changes over time. It depends on whether the economy operates above or below its capacity. When there is little demand, and actual output is below the alleged natural output (also called potential output, and explained in more detail below), policymakers are allowed to make more debt to finance spending programs. This allows to restore growth in recessionary times. In turn, when the economy operates at or above potential output, deficits should be small, to both bring down debt levels and avoid risking inflation. This breathing fiscal space is an elegant mechanism, in theory.

Fatás shows that estimates of potential output themselves depend on past fiscal policy, and this can end up in a vicious cycle: Restrictive fiscal policy leads to less economic activity, and with it, downward corrections of the estimate of potential output; this reduces the perceived gap between actual and potential output; which reduces fiscal leeway and thus makes fiscal policy more restrictive; and on goes the cycle. Or as Antonio Fatas has it, the “fiscal policy doom loop”. This is quite the inelegant mechanism, and unfortunately, it works both in theory and in practice.

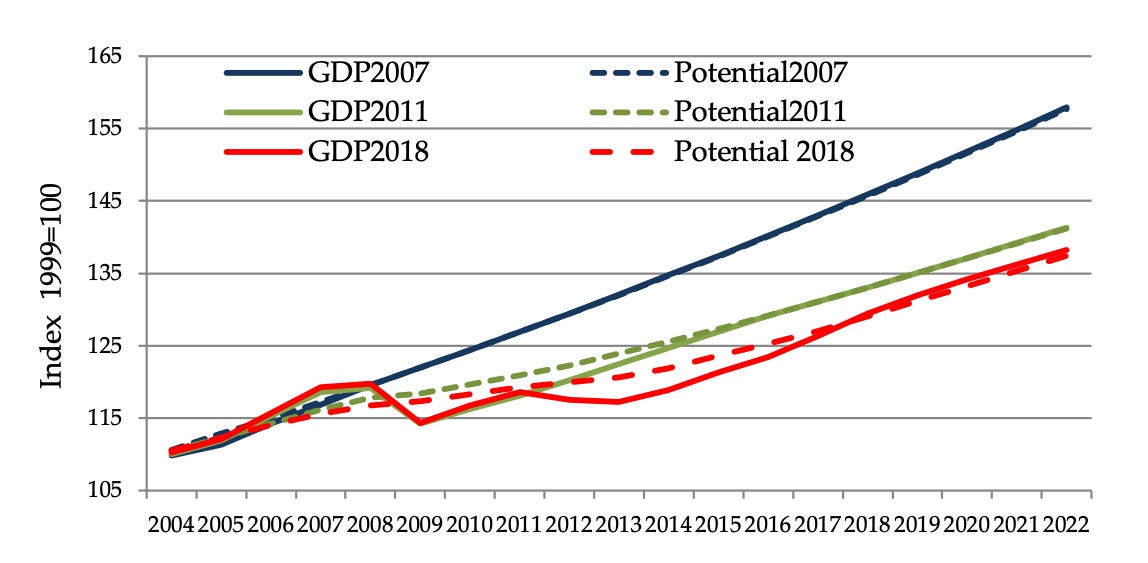

Consider the figure above: the IMF repeatedly downward revised its GDP forecasts throughout the Euro crisis. And this is in significant part due to fiscal policy. Fatas and Summers (2018) quantitatively estimate the effects of this fiscal policy doom loop. They find that

“Every 1% fiscal-policy-induced decline in GDP during the years 2010–11 translated into a 1% decline in potential output by 2015 and even more for 2021.”

And these fiscal policies seem to be one of the determining factors of lost growth after the Great Financial Crisis:

“the short-term fiscal-policy-induced movements in GDP can explain a large percentage of the variation in potential output across countries, as much as 65%”.

Recall that by 2018,

“Relative to the trend that the Euro area was following since the Euro was launched in 1999, GDP today is still far below that level (about 13% below).”

Pretty bad, huh?

One can take away a broader and frankly obvious lesson from this: if you shift your own targets, you will not end up in the place you were initially aiming for. In the case of the GFC, we ended up a good few percentage points of GDP below what we aimed for, and below what we arguably could have achieved. To bring this back to the real world: incomes probably took a larger hit than necessary, and policymakers are, in part, to blame.

Now, what if I told you that a version of the fiscal policy doom loop can equally apply to central banks, it’s just that almost no one is talking about it. Central bankers, just like fiscal policy makers, might be unconsciously shifting their own goalposts. And that it goes unnoticed has a lot to do with modelling: The workhorse model in contemporary macroeconomics, the New Keynesian model, as much as it has brought great progress to macro, plays an unfortunate role in this situation. In particular, many New Keynesian models disregard capital and technology, with far-reaching consequences.

The monetary policy doom loop

Before I begin, let me briefly explain one central concept used in the argument: natural output.

Prelim: What is natural output, anyways?

Natural output is the level of output which would come about if there were perfect competition and no price rigidities.1 You might also call it the production capacity of the economy, or the supply side, or the long run growth path of the economy.2 Natural output in many monetary models is also that level of output which is consistent with stable inflation, so it should be targeted by the central bank. Actual output is the output we observe in reality, induced by demand, which might be above natural output. If actual output is above natural output, we get inflation. My point will be about how central banks impact the supply side or natural output, and how models often disregard that. In the fiscal policy space in particular, “potential output” is often used synonymously with natural output, and I followed that convention in the previous section.

In macro models, what do central banks do?

In basically every paper concerned with monetary policy and that uses the current state-of-the-art New Keynesian model, central banks follow a so-called Taylor rule. This Taylor rule says: If inflation deviates from the target, or actual output (the one we observe and that is induced by demand) deviates from natural output, the central bank raises or lowers interest rates to bring output and inflation back to the target.

Suppose, for example, inflation is above target because there is too much demand and actual output is above natural output. The central bank raises rates, people start saving more, and there is less demand in the present moment. Actual output and inflation return to target.

In most New Keynesian models, central banks only affect actual output, but not natural output. Natural output is supposed to be, you know, natural. It’s determined by technology, the availability of resources, and preferences, things we cannot really influence.

So, like for fiscal policy, we have an elegant mechanism which helps us keep our economy on track.

But again, like for fiscal policy, I believe that central banks do in reality influence the productive capacity, the natural output of an economy. And again, a monetary policy doom loop can be created: raising rates lowers natural output, which makes the output gap larger (actual output is further above natural output), which requires more interest rate raising, which again lowers natural output, and so forth.

There are mainly two mechanisms through which central banks influence natural output, and we’ll have a look at why monetary economists typically and I think unintentionally disregard them. They have a lot to do with a curious absence of capital and technology in New Keynesian (NK) models.

On the absence of technology in the New Keynesian model

A widespread simplification in the construction of NK models is to have labour as the only input in production. They often abstract from capital and technology as central inputs. Luca Fornaro and Martin Wolf have a paper (“The Scars of Supply Shocks: Implications for Monetary Policy”) where they introduce technology into the NK model and think about how that changes things. One thing they show is how a period of high interest rates depresses demand, thereby reducing technology production, and thus shifting the long-run growth path of the economy. They assume endogenous technology production: firms produce technology because they want to make revenues from better or cheaper products. If demand is low, there is little revenue and thus little incentive to produce new technology. By lowering demand today, central banks would worsen the state of technology in the future, and with it, future natural output. Now, if a central bank tries to stabilise actual output around natural output, either as a target in itself or to bring down inflation, then it is the past behaviour of the central bank that determines the level of natural output. The central bank shifts its own goalposts, and perhaps for the worse. If this is a symmetric mechanism, this could obviously also turn into a virtuous cycle! But then, this nice, virtuous cycle can only be made use of if central banks are aware of their own powers with regard to moving the potential output of the economy.

On the absence of capital in New Keynesian models

Another input that is often abstracted from in NK models is capital. Capital produces a second way in which monetary policy shifts its own goalposts.

Remember that natural output is thought to be a function of exogenous things like technology, preferences, and perhaps resource costs. What I introduce is that an additional and quite important factor that determines the natural level of production is borrowing costs. Borrowing costs, especially if they don’t immediately flow back into the economy, are at first sight much like resource costs. They make it less viable to produce stuff.

For the technically-minded, I show the mathematics in the technical notes below. The key point to understand is that in NK models with only labour, natural output really is independent of the interest rate. Once introducing capital, it is not. And this leads to one version of the monetary policy doom loop: if you try to bring down demand by raising interest rates, that also reduces natural output or supply, and demand and supply enter a race to the bottom until demand finally catches up and inflation is stabilised.

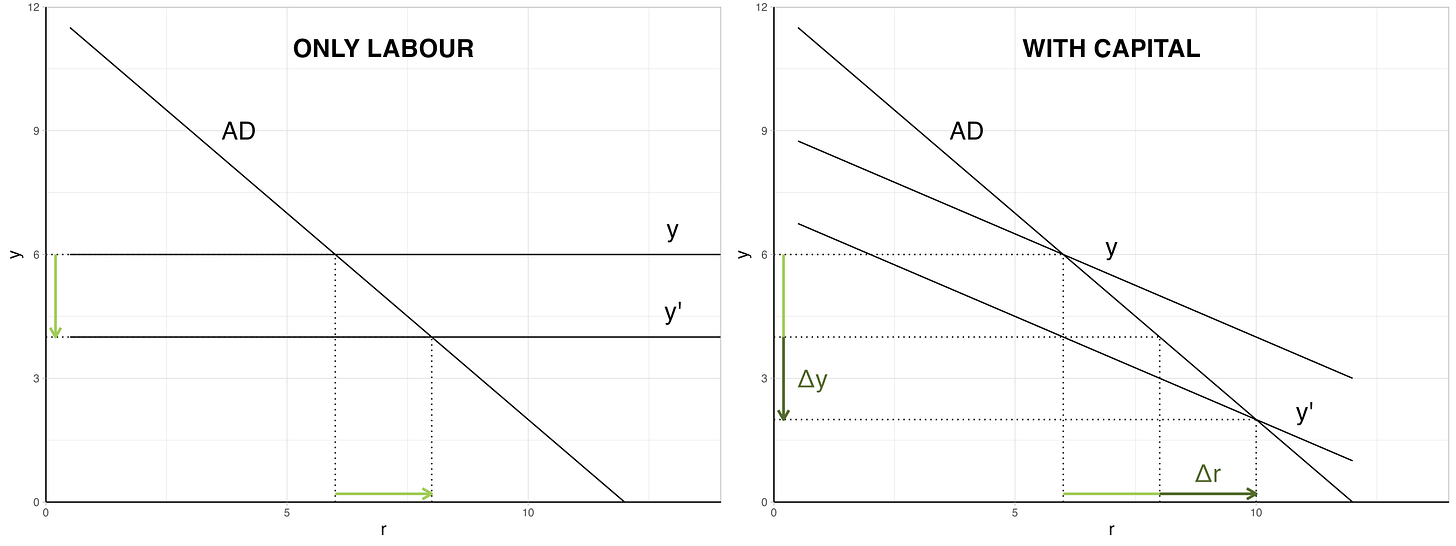

The figure below shows the mechanism. The interest rate is on the x axis, output on the y-axis. Aggregate demand is downward-sloping in the interest rate: people consume less today if interest rates are higher. Then there is natural output. In the left panel, natural output is independent of the interest rate (as in standard NK models) and therefore horizontal. The two curves intersect at the interest rate which will bring inflation and output on target.

Suppose a supply shock hits the economy, and natural output shifts downward. The new intersection of demand and output is at a higher interest rate: a raise of the interest rate is required to bring down inflation, by lowering demand and thus bringing actual output to natural output. This is the way the monetary economist would like things to work.

Now consider the right-hand-side panel. Here, nautral output slowly declines with higher interest rates. This is because higher borrowing costs (the interest rate is higher) reduce the productive capacity of the economy. Suppose the same supply shock hits the economy, downward-shifting natural output. Check out where the new intersection of demand and output is, that is, where the new interest rate is that stabilises inflation: at a lower level of output and a higher interest rate, as compared to where it was in the left panel. Because natural output declines in the interest rate, the central bank basically has to produce a larger output drop so that aggregate demand can chase down natural output. As doom loop as it gets, if you ask me.

What to make of this

Both in the short and the long run, central banks influence natural (or potential) output. They do this through their effect on borrowing costs and on the production of new technology and, therefore, growth.

Central bankers (and fiscal policy makers) should be aware that they are shifting their own goalposts. They should consider that they not only influence demand on a business cycle timescale, but that they also determine long-run potential output. For central bankers, this might imply that a more accommodative stance towards inflation is appropriate, given that fully bringing down inflation requires restricting not only demand but even the productive capacity of an economy, both in the short and in the long run.

Of course, perhaps central banks have models and methods more sophisticated than what we see in most of academic monetary economics. Maybe they do know their power. But then this raises a question about our institutional setup. Consider the primary mandate of the ECB: Stabilising inflation. In a world where monetary policy has no long run effects on the productive capacity such a limited mandate might not be an issue of concern. But if monetary policy is also responsible for shifting potential output, should we not give central bankers a mandate that tells them what to do with that power?

The ECB of course does have a secondary mandate of supporting the European Union’s general economic policies, which is generally understood to include supporting growth. It is unclear, however, what that support exactly looks like. It is even more unclear whether the ECB gives enough weight to this secondary mandate, particularly in light of the amount of influence they have over growth.

We (we Europeans) should, at some point, probably tell the ECB what to do with its influence over the supply side.

Acknowledgements

Elina Dilger and Leon Ahlborn much improved this text with their comments, and Elina also with her drawing.

References

de Boer and van’t Klooster (2021) The ECB Cannot Ignore its Secondary Mandate

Fatás (2019) Fiscal Policy, Potential Output and the Shifting Goalposts

Fatás and Summers (2018) The permanent effects of fiscal consolidations

Fornaro and Wolf (2023) The scars of supply shocks: Implications for monetary policy

Technical Note

Some more explanation on natural output and its dependency on or independence from the interest rates. In sufficiently simple models, one can find analytical representations of natural output (see, e.g., Blanchard & Gali (2007) Real Wage Rigidities and the New Keynesian Models. Notice they distinguish between efficient output (output under perfect competition and flexible prices) and natural output (flexible prices but monopolistic competition), but for now it suffices to say that the two can be identical given some subsidy that corrects for the monopolistic distortion). If one excludes capital and thus borrowing costs, natural/efficient output is really just a function of external parameters and technology. However, once you introduce borrowing costs, efficient output falls if the interest rate increases.

Check out the following derivation of efficient output in a model with labour and capital in a classic Cobb-Douglas production function. For simplicity, labour supply is fixed. The efficient output, therefore, just has one equilibrium condition, namely that the marginal productivity of capital (MPK) equals its marginal cost. Marginal cost is the interest rate. So, let’s find the marginal productivity of capital.

Efficiency requires:

Substituting into the production function gives:

Thus efficient output is:

Notice that efficient output is a negative function of the interest rate. We can also see what would be the case if capital didn’t play a role. This is the case if alpha is zero. The term in brackets is raised to the power of zero, so it’s one, so efficient output is just equal to the exogenously given labour level and thus independent from the interest rate.

Monetary wonks may prefer to denote the output induced by perfect competition and no nominal frictions as “efficient output”, not “natural output”, and reserve the latter for the output induced by no nominal frictions but monopolistic competition. For the sake of this text, the difference between the two does not matter. Indeed, the same wonks will know that the difference in fact is none in New Keynesian models, if the government adopts a subsidy correcting for the distortions from monopolistic competition, and if there are no real frictions.

This level is pareto-efficient, which is a notion of a welfare optimum, where no one’s welfare can be improved without negatively affecting someone else.

Couldn't agree more. This idea of central banks shifting their own goalposts is such a sharp observation. It really makes you reflect on the deep challenges of managing any complex system, where our interventions so often have unforseen ripples. Makes you wonder if an AI could even untangle it all.